Grading on Progress

Grades are typically set in absolute terms: you either get the points or you don’t. It doesn’t matter where you started, it doesn’t matter how fast you learn. You either get the points or you don’t. Grading on progress takes a different approach to certifying achievement.

Intuitively, it makes sense, if two people made the same amount of progress, they should get the same reward. But the way in which we interact with grades is different. We are trying to get a quantity that represents achievement. Particularly, we are interested in the degree of achievement of the learning goals set at the beginning of the course by the professor and the students. I understand that this treats knowledge as a commodity that can be obtained and accumulated. While I believe that reality is a bit more complex, I think this is a good starting point for our discussion.

So…How much do students learn anyway? That is a difficult question, let’s simplify by assuming some conditions:

- We have set achievable learning objectives/goals.

- We test often.

- Our testing method is valid and graded fairly.

- We obtain an accurate representation of whatever is inside our students brains (aka “knowledge”).

- Students put roughly the same amount of effort.

- Students put enough effort for the task.

- Our teaching method is effective in increasing student’s knowledge of the subject.

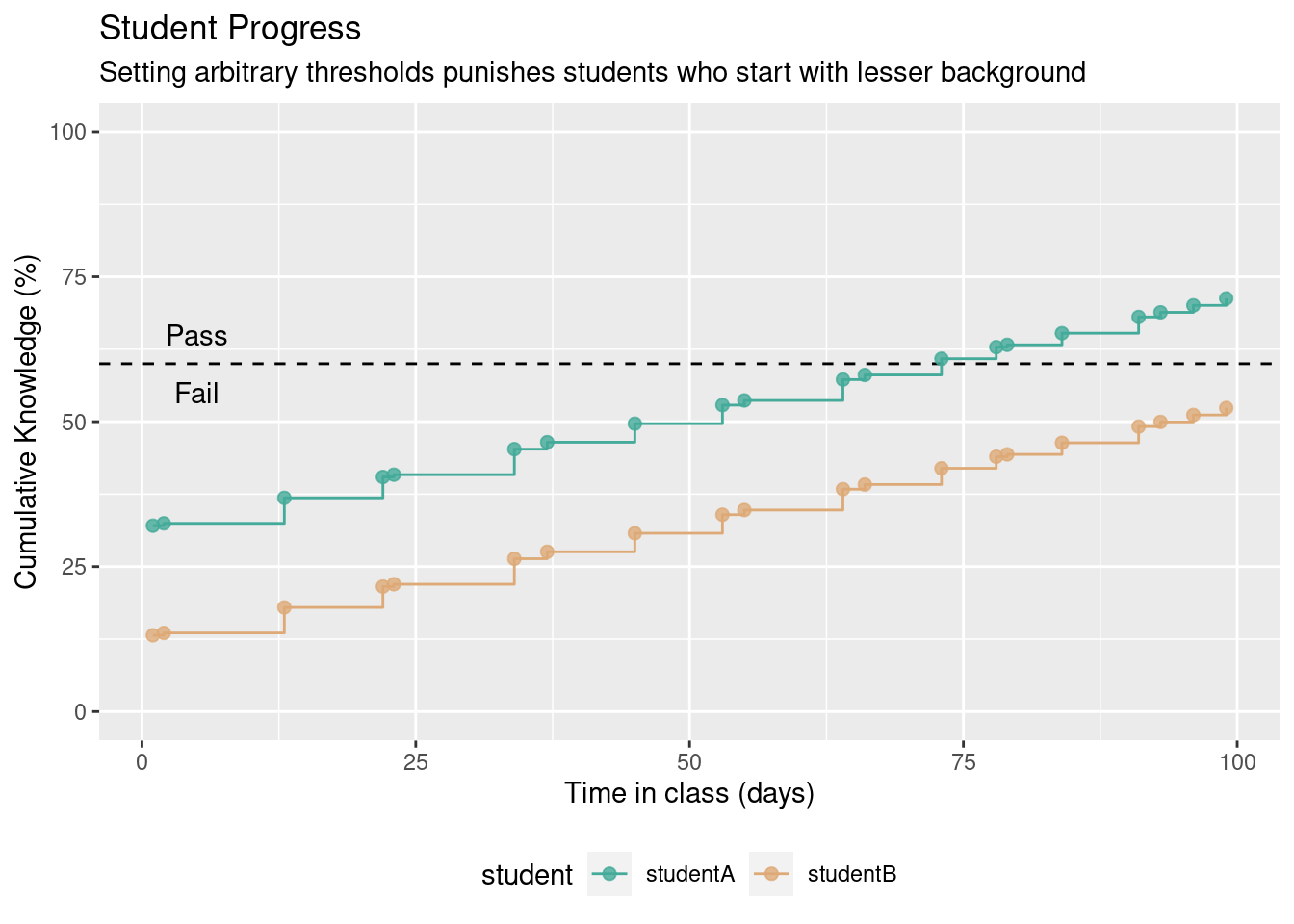

If these were true, we would then likely see that our students make progress at roughly the same rate. But progress rate has its caveats. Let’s choose two students. It happens that one of them came to the course with bit more knowledge on the subject matter than the other. Given the assumptions listed above, here’s one possible outcome.

We can look at the performance summary in the following table. Both students performed similarly (change column) , but they didn’t come with the same background (min column). Thus, the cumulative knowledge/score is higher for studentA (max column).

| student | min | max | change |

|---|---|---|---|

| studentA | 32.06 | 71.26 | 39.2 |

| studentB | 13.16 | 52.36 | 39.2 |

What to do?

Grading on progress put us in a conflict. If measuring progress, both students should be graded equally. But a criterion-based method tells us otherwise. Whenever there’s a critical amount of knowledge, it might be the case that some students fail to achieve it. Lowering the bar is not an option. Problems like this one do not arise because we chose the limit at 60%. Problems like this one arise because the arbitrary limit exists. There are options to solve the Pass/Fail issue. We can switch to setting a limit for the amount of progress students make in our classroom. However, setting an arbitrary limit for the amount of progress students make will still generate problems. Most importantly, in such a method, passing students fail to achieve criteria.

Maybe our assumptions are wrong, maybe not all the students learn at the same rate. Let’s take another case.

Let’s take a look at the summary table.

| student | min | max | change |

|---|---|---|---|

| studentB | 13.16 | 52.36 | 39.20 |

| studentC | 78.55 | 78.59 | 0.04 |

In this case, if we chose to grade on progress, we would produce a counter-intuitive result. Absurd example aside, we can argue that studentC is overqualified for the course. But the truth is, this student hasn’t mastered the material yet. Wouldn’t it be great if all students got to 100%?

Mastery

Wait a minute… Shouldn’t we aim to get our students to know all the material? Aiming for mastery implies that the bar is at 100%. It also means that advancement to the next level requires achieving all learning outcomes.

This might sound as too tough, but learning new material involves adding the new information to the network of already established concepts in our brain. We can think of it as adding a new floor to a building. We can’t afford to let gaps in knowledge propagate year after year, just as we can’t add floors to a skyscraper with terrible foundations or gaps in the middle. We can’t afford gap propagation, even for small gaps. Salman Khan explains it better than me here, if you get anything from this article, I wish it’s the next quote:

Teaching for Mastery is not a nice to have, it’s a social imperative. - Salman Khan

The path

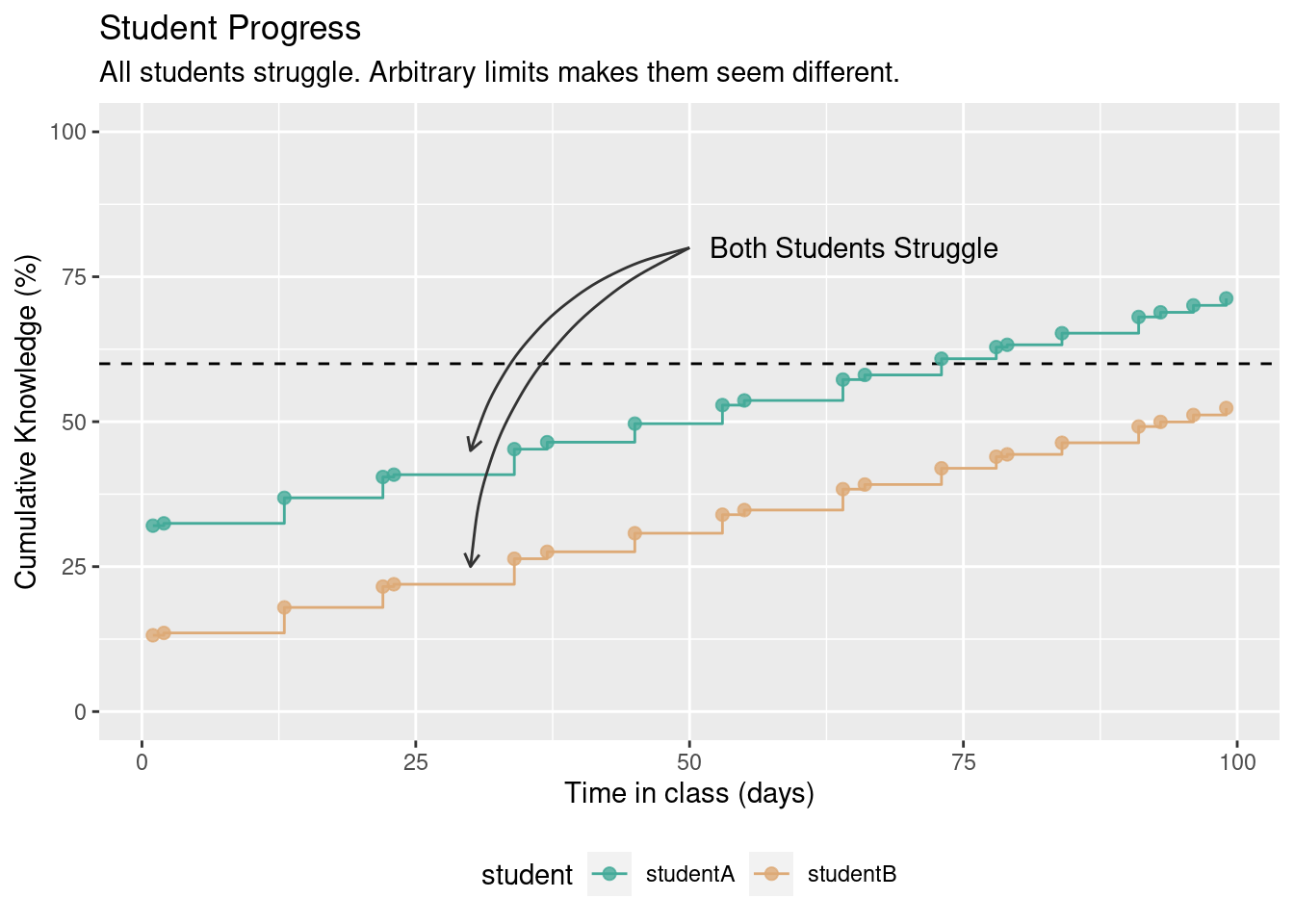

The path matters. We can think about learning in terms of packets of knowledge, cumulative unlocked skills or mini level-up moments. Let’s take a look at the journey of studentA and studentB.

These students are very similar. In fact, we can see them struggling to get some concepts (check the colored region). Still, an arbitrary limit makes them look different.

The time constrain

Teaching for mastery requires that we flip over the constrains. Normally, we would constrain on time. Students have x weeks to get the cumulative percent that we considered good enough. That creates gaps in knowledge. Forcing students to advance to a new level will propagate those gaps.

Instead of advancing students with gaps in knowledge by constraining time, we could constrain knowledge. All students should get to 100%. If students needed more time to acquire a particular skill or solve a particular type of problem, they should be allowed to take it. By teaching this way, we reinforce resilience and promote the correct mindset for problem solving.

Using current technologies, it is possible to teach individualized lessons and track individual knowledge1. If we use this strategy we need to deal with differences between a fast learner2 and one that got stuck in a concept for longer. Here’s how the paths would look like.

We can see that one student mastered the content before the other. There’s no problem with that. In fact, speed differences already happen in the current system and faster students disengage because there’s no further development to go after. The big advantage of teaching for mastery is that we have options, at the moment marked with an asterisk * we could:

- Promote the student to the next level.

- Promote the student to be

peer mentor. - Both options at the same time.

The first option is the more individualistic. If one made progress at a faster pace, one should be allowed to move forward with more content. Here we have a first difference with the current system. Currently, students are put together by age, as if that were the only variable that determined their capabilities. Teachers have to go a long way outside the comfort zone to give extra assignments to these students. Faster students become a burden instead of a bliss. When the content is already being delivered individually by design, there is no extra effort to pump more advanced material to fast learners.

The second option allows the student to engage in fulfilling activities and enhance even more their confidence with the topic. To be able to mentor a student or teach a topic, you have to have mastered the content and be able to communicate it in a way the other mind can understand. Fostering empathetic relationships brings a social element to the classroom, priming students to a real-life experience in collaborative environment. Additionally, students that teach interact with the topic in different ways than traditional students. Peer mentors gain a complete new dimension by having to exercise different approaches to solve a problem or convey an argument.

There are good arguments for having classrooms with small age differences. Sociability among students is heavily influenced by age and there are particular moments in development where two years of difference means a lot. Thus, exploring both options could be a good trade off for students. Given a student was able to master the material, now she has the opportunity to continue forward. But she also has the responsibility to help fellow students who are struggling. It sounds like a win-win situation to me.

Footnotes

Visit Khan Academy↩︎

When I say fast I do not mean to generalize, it’s just for the sake of argument. Fast as in “a student that took less time to master that particular material”.↩︎

Reuse

Citation

@online{andina2018,

author = {Andina, Matias},

title = {Teaching for {Mastery}},

date = {2018-01-05},

url = {https://matiasandina.com/posts/2018-01-05-teaching-for-mastery},

langid = {en}

}